As the old saying goes, repeat something enough times and it becomes accepted as the truth. It’s starting to seem this way when it comes to the potential savings that may be realised when moving to virtualisation. Physical consolidation and better utilisation has got to be a winner all round, right? Or does it?

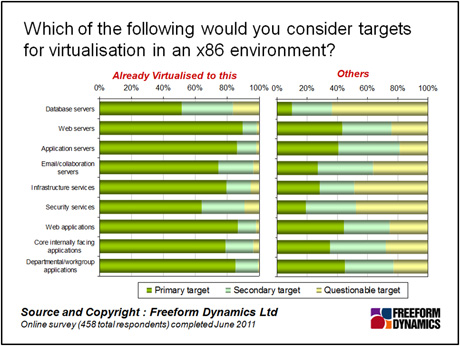

There is no denying that virtualisation has caught on in most organisations that are mid-sized and above. Our latest survey shows high adoption rates of virtualisation for consolidation of x86 servers, with the intent in future to further increase its use as well as to look to more advanced solutions such as forming a dynamic private cloud. Those who have implemented virtualisation have tended to virtualise a wide variety of workloads, be they lightweight departmental applications, critical infrastructure services such as Active Directory or DNS, or demanding applications such as Exchange Server.

One significant exception is the virtualisation of database servers. This lags due to issues such as performance predictability and database licensing costs for virtual machines, as seen in the chart below. However, even here the trend we see is towards increasing virtualisation over time.

All of this points to virtualisation becoming an integral part of the IT infrastructure in the future. Some organisations are already adopting an approach of “virtual by default, physical by exception” for application or service deployments, and from conversation we have this is likely to increase. In future, the provisioning, deployment, change management and operational control will be geared towards this, making virtualisation a core pillar of IT strategy.

If we look in a bit more depth, however, we can see some worrying trends emerging as more and more experience is gained with implementing virtualisation. Some of the challenges are traditional issues that are highlighted or exacerbated by virtualisation. Disjointed management is one, as is the issue of joint procurement and purchasing, which could easily be classified as the “That’s my server and I’m not sharing it” problem.

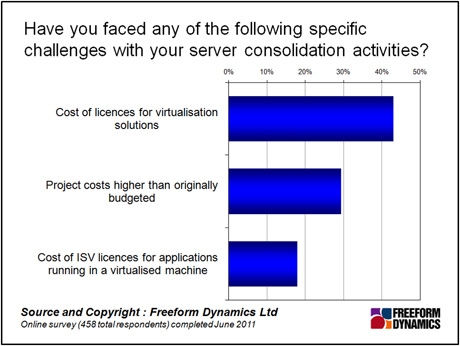

But it’s the commercial and financial side of things that is becoming the biggest issue for consolidation and virtualisation. We know from our research that licensing is a perennial problem for IT, so it’s no surprise that this is also an issue in virtualised solutions. However, it’s no longer the cost of licensing ISV software in a virtual environment that is identified as the main issue – many software vendors have been tweaking terms to work ‘better’ with virtual environments. Instead, as you can see in the chart below, it is the virtualisation platform itself that is becoming a primary cost inhibitor – and this should be ringing alarm bells for anybody building out a virtual or cloud environment.

The virtualisation market is still reasonably new, but is consolidating down to a small number of influential providers. Pricing models are still quite dynamic, with fairly rapid and major changes coinciding with new product releases.

Some of these changes can have significant impacts on the cost of the virtualisation layer itself – particularly if they target the changes in server configuration that have come about as a result of optimising for virtualisation to increase the licence costs. Some of these metrics might include processor core count, installed memory or networking capacity.

The end result is that what should be a cost effective way to increase the utilisation of hardware and improve the management and provisioning of workloads at a fraction of the cost of purchasing new hardware is, in some cases, rivalling the cost of buying the new hardware itself. This can be a problem if the virtualisation solution costs then start to approach or even exceed the expected cost savings of the rest of the hardware and software used in the solution.

This issue of cost increases would not be a problem in an open environment where there is freedom to choose and migrate between suppliers. However, if the virtualisation environment is intrinsically tied to a particular vendor’s technology or management tools, it can become a difficult situation to manage.

One choice if locked into a vendor is to trying to negotiate a better deal – but few companies have the individual influence to really manage this. Another option is staying with the existing platform and licensing terms if that is possible. Whichever way you look at it, platform lock-in restricts the ability to adapt or respond.

Moving to another provider may offer some price advantage, but will entail a migration cost, migration risk and no long-term certainty that the pricing will remain advantageous. The potential for future vendor lock-in will still be a problem.

None of us really want to give up on virtualisation and move back to physical machines – the long-term benefits are real and can be substantial providing the costs are managed and don’t spiral out of control.

The long-term strategy around virtualisation should look to create a framework that is independent wherever possible of vendor-specific technologies. This will mean that a virtualisation solution is not centred on the hypervisor and associated proprietary management technologies. Ideally, the management of virtualisation should be abstracted and independent, allowing alternative solutions to be slotted in with a minimum of integration and fuss.

Not only will this allow choice as to the most cost effective solution should pricing changes occur, it will also allow the flexibility to choose the most appropriate virtualisation technology for the job in hand, rather than forcing all workloads to run on the same platform regardless.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW ORIGINAL PUBLISHED ON

Content Contributors: Andrew Buss

Through our research and insights, we help bridge the gap between technology buyers and sellers.

Have You Read This?

From Barcode Scanning to Smart Data Capture

Beyond the Barcode: Smart Data Capture

The Evolving Role of Converged Infrastructure in Modern IT

Evaluating the Potential of Hyper-Converged Storage

Kubernetes as an enterprise multi-cloud enabler

A CX perspective on the Contact Centre

Automation of SAP Master Data Management

Tackling the software skills crunch